The 2007 financial crisis has reignited the discussion on crises, their origin and possible remedies.1 At present the most influential thesis on the left sees the crisis as caused by underconsumption and recommends Keynesian policies as a solution. This paper argues that we should understand the crisis from the perspective of Karl Marx’s “law of the tendential fall in the average rate of profit” (ARP), for short “the law”. Its characteristic feature is that technological progress decreases the rate of profit, rather than increasing it as is usually assumed. Let us see why.

The law in a nutshell

The law’s essential features are as follows:

(1) Capitalists compete against each other by introducing new means of production incorporating new technologies. This is not the only form of competition but it is by far the most important one for understanding the dynamics of the crisis.2

(2) The new means of production increase the efficiency (output of use values per unit of capital invested) of the technological leaders in the

productive sectors.

(3) At the same time, the new technologies are designed to replace labourers with means of production. Therefore the technological leaders’ proportion of capital invested in means of production relative to that in labour power, the organic composition of capital, increases. Unemployment follows.

(4) Since only labour creates value, less labour power employed means less (surplus) value created by high-technology capitals. All other things being equal, the ARP falls: ‘‘The rate of profit does not fall because labour becomes less productive, but because it becomes more productive”.3 Notice that it is the rate of profit and not the mass of profits that falls. The latter can increase when the former falls. Conventional economics cannot see that it is the very dynamics of the system, ie technological competition, that causes the fall in the ARP and thus crises, because implicitly or explicitly it reasons only in physical or use value terms.

(5) It follows that a greater quantity of use values incorporates a smaller quantity of (surplus) value, ie that falling profit rates and rising outputs are two sides of the same coin.

(6) The technological leaders perceive increased productivity as the way to realise higher profit rates. They do not know that their workers produce less surplus value. However, rises in the rate of profit of the technological leaders come about because they appropriate surplus value from two sources. First, from other sectors, if the new products attract purchasing power from other sectors. Initially those suffering as a result will be the weaker capitals in those other sectors. Second, from the technological laggards in their own sector because the more productive capitals can sell at the same unit price a greater output per unit of capital invested. So the technological leaders’ rate of profit rises, while that of the laggards and the ARP falls. Eventually, capitalists who cannot innovate go bankrupt.

(7) Like all laws of development, this one is tendential. The same factor, technological innovation, determines both the tendency (the increase in the organic composition and the resulting fall in the ARP) and the

countertendencies. Several countertendencies can and do coexist.

(8) The tendency is such because it is kept back and delayed by the countertendencies. But it eventually emerges when the countertendencies exhaust their counteracting power. Then the crisis emerges. There is a sudden jump in bankruptcies and unemployment whose real scope had not been allowed to manifest itself (fully) by the countertendencies.

(9) It follows that the tendency continues to operate even if temporarily reversed by the countertendencies. This becomes empirically visible when the ARP is computed in the absence of the countertendencies.

(10) The crisis creates the conditions for the recovery. The recovery emerges when these conditions have become sufficiently strong. Periods of growth alternate with period of crises.

(11) Since technological competition is the dynamic of capitalism, the economy tends necessarily towards an increase in the organic composition of capital, a decrease in the ARP, and crises. But the concrete shape of the ARP is the result of the interplay of the tendency and its countertendencies.

Empirical evidence

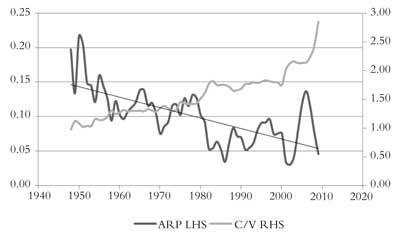

Initially, the focus will be on the profits realised, rather than those produced, in the productive sectors.4 These are the profits that can be capitalised as further productive capital, and this capitalisation (or lack of it) is the basis for an acceleration or deceleration of the economy and thus of the cycle. Moreover, one of the theses of this work is that the cause of the financial crises is to be found in the decreasing profitability of the productive sectors. The computation of the ARP for the whole economy would not allow the empirical substantiation of this thesis. Figure 1 focuses on the productive sectors (see the Appendix). This chart shows both a secular (from 1948 to 2009) falling trend in the ARP and a secular rising trend in the organic composition of capital (c/v), in conformity with the law.5

The ARP peaks in 1950 (22 percent), reaches a trough in 1986 (3 percent), rises to 14 percent in 2006 and drops vertically to 5 percent in 2009. The organic composition rises from 0.98 in 1948 to 2.85 in 2009.

Within the secular downward trend two long-term but shorter cycles can be discerned—from 1948 to 1986 and from 1987 to 2009. The ARP tends to fall in the first period but rise in the second. Some authors have concluded that if the system can be in a (financial) crisis while the ARP rises, as in the 1987-2009 period, the law can be discarded as a explanation of crises.6 Other authors correctly deny this but from a methodological standpoint different to what I consider to be Marx’s own, as set out in the 11 points above.7

Figure 1: Average rate of profit (ARP) and the organic composition of capital (C/V) for the productive sectors, 1948-2009

Figure 1 shows the ultimate cause of crisis, ie the tendency of the organic composition to rise and thus the tendency of the ARP to fall over the whole secular period. The two trends move necessarily in the opposite direction, as in Marx’s theory. But at each moment and for shorter periods the organic composition determines the movement of the ARP through its interaction with the countertendencies. It follows that:

(1) There is not a mechanical, inverse relation at each point in time between the organic composition and the ARP.

(2) The secular downward tendency keeps driving the economy towards crisis even when in the shorter period its effect is temporarily suspended and reversed by the countertendencies.

This paper considers three countertendencies. The first is the fall in the organic composition. New technologies decrease the unit value of the output, including the produced means of production. In the following production period, the cheaper means of production can cause the organic composition to fall and, on this account, the ARP to rise. The critics conclude that the effect of technological innovations on the organic composition and thus on average profitability is indeterminate.8 Figure 1 above shows incontrovertibly the secular rise in the organic composition in spite of short-term countertendencies. Marx explains why in the Grundrisse: “What becomes cheaper is the individual machine and its component parts, but a system of machinery develops; the tool is not simply replaced by a single machine but by a whole system… Despite the cheapening of individual elements, the price of the whole aggregate increases enormously”.9 As for raw materials, their cheaper production contributes to the rise in the ARP when they become the inputs of other production processes. However, this countertendency is overpowered by an increase in the organic composition both of the processes from which they are outputs and of those other processes for which they become inputs where the increasing fixed capital also increases circulating capital.

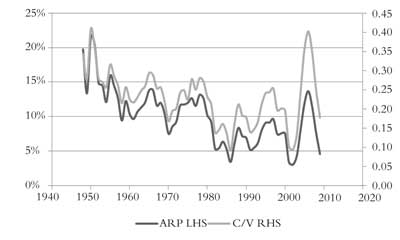

The second countertendency involves the rate of exploitation. Figure 2 shows that the ARP and the rate of exploitation exhibit roughly the same pattern. This indicates that in the period from 1987 to 2009 the ARP rises in spite of a rise in the organic composition. This is due to the rise in the rate of exploitation.

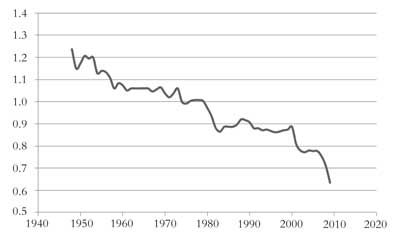

What would the ARP have been in the absence of a rise in the rate of exploitation? In Figure 3 the average rate of exploitation has been computed for the 1948-86 period and the ARP has been computed for the whole secular period according to this average, including the 1987-2009 period. This procedure shows what the ARP would have been in the 1987-2009 period if the rate of exploitation had not risen above the average of the previous period. It thus isolates the course of the ARP from the increased exploitation in the 1987-2009 period. Figure 3 shows that the ARP would have fallen dramatically. Therefore the ARP has risen because the rise in the rate of exploitation has overpowered the rise in the organic composition, because this countertendency has overpowered the tendency. In 2006 the ARP was 14 percent but it would have been

8 percent without a rise in the rate of exploitation.10

Figure 2: Average rate of profit and the rate of exploitation (P/V) in the productive sectors, 1948-2009

Simply put, the rise in the ARP since 1987 has been due to an unprecedented jump in labour’s exploitation.11 This is an indication of the magnitude of the defeat of the working class in the neoliberal era. The sad peculiarity is that the working class has not yet been able to rise again and claim a larger share of the new value produced. The onslaught continues. Thus, in the US in the so-called recovery after the Great Recession of 2007-9, mid-wage occupations were still 8.4 percent below pre-recession levels of employment, compared to higher-wage occupations which were 4.1 percent down and lower-wage occupations which were 0.3 percent down. “Of the net employment losses between the first quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of 2010, fully 60.0 percent were in mid-wage occupations, 21.3 percent were in lower-wage occupations, and 18.7 percent were in higher-wage occupations”.12 The view that the increase in the rate of exploitation cannot be considered a countertendency because it has lasted since 1987 is based on a misunderstanding. A countertendency is not defined by, and is independent of, its duration. It persists as long as the conditions for its existence persist, in this case the defeat of the US (and the world’s) working class. This latest broadside against the validity of the law of the falling profit rate, like the previous ones, has been fired with blank cartridges. The problem is that some believe them to be live ammunition.

Figure 3: Average rate of profit in the productive sectors if the rate of exploitation had continued on its 1948-86 trend

The third countertendency is the migration of productive capital to the unproductive sectors where individual capitalists realise higher profit rates and the ARP rises but only under certain conditions. A distinction should be made between the commercial, the financial and the

speculative sectors.

Take commercial capital first. Capitalist production is at the same time a labour process, a transformation of use values into different use values (a real transformation) and a surplus value producing process—the expenditure of labour by the labourers for a longer time than would be required for the reproduction of their labour power. Since commercial capital does not transform use values (it deals with commodities without changing them, ie its labourers do not perform real transformations), it is unproductive. Thus the value accruing to it must be appropriated from the productive sector. If the commercial labourers buy commodities at below their value, they sell them at their value, and if they buy them at their value they must sell them at above their value. The more value that is gained by one sector, the greater the value lost by the others and vice versa. The transformation carried out by commercial labour is formal because it transforms (a) a real value into its representation, money, and vice versa, and (b) one form of representation of value into

a different form.

As an example, consider the work of drawing up the sale transaction (eg a title of ownership of a house). It could be held that the paper on which the contract is written is more valuable than a blank sheet of paper because of the ink consumed and the clerk’s labour that have gone into that writing. However, that paper is in fact more valuable because of the value it represents. Without that house, the paper is essentially worthless. The notary public might ask a higher fee for four rather than for two hours of work because unproductive labour mimics productive labour and is rewarded in terms of labour time. But this does not make it productive labour. Since the value appropriated by the unproductive capitalist must be greater than the value of the labour power employed, the harder and the longer commercial labour works, the greater commercial capital’s profits. Commercial labour is exploited in the sense that it appropriates (rather than producing) on behalf of the commercial capitalist more surplus value than the value of its labour power. Can commercial profits raise the ARP and thus form a countertendency?

(1) If the commercial capitalists purchase commodities from the industrial capitalists at (or below) their value and sell them to other capitalists above (or at) their value, there is redistribution of value within the capitalist sphere and the ARP is unchanged.

(2) If commercial capitalists sell them to the workers at their value, there is no redistribution of value but realisation of the value of the means of consumption.

(3) If commercial capital sells them to the workers above their value, there is an exchange of value for a greater quantity of a representation of value (money). In this case there is appropriation of (a representation of) value from the workers. The ARP rises and commercial capital has a countertendential function.

Consider next financial capital. If profitability falls in the productive sectors, capital moves to the financial sectors where higher profits can be made. This movement feeds speculative bubbles and ultimately the financial crises. The origin of the financial crisis is thus to be found in the productive sphere. The opposite thesis holds that financial crises originate in the financial sectors.13 That thesis is based upon three arguments.

(1) The latest financial crisis exploded in a period of rising profitability, so the productive sphere cannot be the cause of the financial crisis. This argument has been dealt with already.

(2) Financial and speculative activities produce value and surplus value because money is invested in capital that begets more money than the money invested. The distinction between productive and unproductive labour should be abandoned and with it Marx’s argument. This thesis overlooks the fact that there is no real transformation in the financial sectors.14 The thesis does not explain why two parties exchanging the same commodity at the same price or at an ever higher price increase that commodity’s value and surplus value.

(3) The financial crisis has first emerged in the financial and speculative spheres due to ballooning debts and policy mistakes (eg deregulation, and the attendant housing bubble and the subprime mortgage crisis of 2007). From there it has spilled over into the real economy. This is a subjective theory of crises. However, if the same mistakes keep being made time and again, there must be objective forces that compel economic agents to repeat those mistakes. Moreover, the financial crisis can affect the real economy only if the latter is already in a precarious situation.

Finance capital can be subdivided into money capital and loan capital. In money capital, money, a representation of value, becomes a commodity that can be bought and sold or exchanged for other representations of value. These are formal transformations, from a form into a different form of representation of value, for example through trading different currencies. This labour is unproductive.

Loan capital, or interest-bearing capital, differs both from commercial and from money capital in that the basic object of its transactions is a representation of debt rather than of value. It engages in transformations from a representation of value (eg money) into a representation of debt (bonds, derivatives, etc), from a representation of debt into a different form of representation of debt (from mortgages into mortgage-backed securities), or from a representation of debt into a representation of value (the sale of a mortgage). These representations of debt are called by Marx fictitious capital: “With the development of interest-bearing capital and the credit system, all capital seems to double itself, and sometimes treble itself, by the various modes in which the same capital…appears in different forms in different hands. The greater portion of this ‘money-capital’ is purely fictitious”.15 For example, the same money (capital) appears first as a mortgage and then as a mortgage-backed security. To consider these representations of debt as (financial) assets, as wealth, means to take the point of view of financial capital for which debt is wealth. No wonder, then, that economic theory considers the creation of credit and thus of debt as creation of money “out of thin air”, an absurd notion.

Titles of credit/debt have no intrinsic value. However, they have a price. Take a bond. Its price is given by the capitalisation of future earnings and thus depends on the rate of interest. Marx refers to this as the “most fetish-like form” of capital because it seems that it is capital that creates surplus value, not labour.16 Loan capital is fictitious capital, not because its price is due to the capitalisation of future earnings, but because it is a representation of debt.17

If loan capital is fictitious, its profits are fictitious too. They are fictitious not because they do not exist (as in some fraudulent accounting practices). They are the appropriation of a representation of value (money), and in this sense they are real. But they are fictitious because this appropriation springs from a relation of debt/credit rather than production. Financial capital sells titles of debt with no intrinsic value for a representation of value, money. It appropriates value. If money is appropriated from other capitals, the ARP is unchanged. If it is appropriated from the workers, it increases. Let us provide one example.18

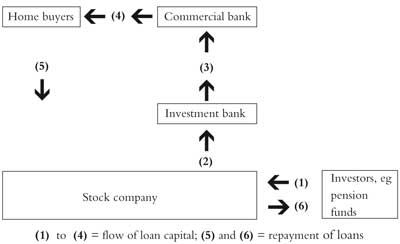

Figure 4: Mortgage-backed securities

Suppose a commercial bank grants a loan to a borrower for the purchase of a house. Traditionally, the commercial bank could use the depositors’ money to grant a loan that would be paid back by the debtors. It was the bearer of the risk in case of the borrower’s default. With the ballooning of the speculative sector (see below), banks have resorted to a different strategy in order to shift the risk of default to others, namely, to labour (conveniently called “the public”). A commonly used practice is as follows. The commercial bank (or a broker) bundles together many mortgages and sells them (it sells the right to collect principal and interest) to another bank, an investment bank. The commercial bank renounces the right to collect the mortgages’ principals and interest payments

from the home-buyers but acquires the right to receive the capital it needs from the investment bank. The commercial bank accepts a discount on its loan because it can collect now rather than in the future and, at the same time, it avoids the risk of possible defaults on mortgage

payments. The commercial bank thus loans capital which is not its own. The investment bank must provide the capital for the commercial bank but it does not have it. In order to find that capital, the investment bank creates a corporation to which it transfers those loans in exchange for the capital it needs to pay the commercial bank. To get that capital the corporation issues bonds which the investment bank sells to hedge funds, pension funds and so on. In this way, the company gathers the required money which it transfers to the investment bank. This, in turn, uses that capital to pay the commercial bank which then loans that money to the home purchasers. The bondholders provide indirectly the capital for the home loans and the homeowners repay the loans to the stock company that, in turn, uses it to pay principal and interest to the bondholders. If the demand for those bonds is sufficiently high, their price exceeds the value of those assets (the future stream of payments for principals and interests) and the bond issuer makes a profit. These bonds are mortgage–backed securities, that is, loans that have been securitised. They are one of the many forms of derivatives, that is, contracts that derive their value from an underlying asset (the mortgaged houses, in this example).

In the case of a default, if the stream of payments to the stock company stops, the pension fund’s demand for credit-restitution cannot be met and the depositors lose their pensions.19 In essence, this is the class content of this type of derivative.

Loan capital is intertwined with speculative capital. The origin of modern speculative capital can be traced back to the fall in 1971 of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates anchored to the US dollar.20 In principle, prior to then, foreign capitals’ income from exports to the US was bought by foreign central banks, which then purchased gold from the US Federal Reserve. That system worked as long as the US held absolute economic power and thus competitive advantages. But it could not hold as the US balance of trade deteriorated and the US economy declined in relative terms. By 1971 foreign central banks held $50 billion in reserves while the gold stock of the US was only $10 billion.21 The system of fluctuating exchange rates that emerged set the condition for modern speculative capital. Its basic features are:

(1) Its extreme mobility from one sector of the economy (“market”) to another, ie high volatility.

(2) Its huge scale, even bigger than the finances of many states.

(3) Its almost complete reliance on loan (credit) capital, ie high leverage rates.

(4) Arbitrage (the practice of taking advantage of price differences between different markets) as its specific form of speculation.

(5) Its self-destructive movements: speculative capital eliminates the opportunities that give rise to it.

Modern speculation will be considered again further down in discussing the speculative bubbles. Here suffice it to mention that the arguments submitted above concerning unproductive capital apply tout court to speculative capital.

Lack of demand or lack of profit?

Many of the present challenges to Marx’s law are based on underconsumptionism, the view that the crisis is the outcome of a decreased demand for consumption goods, which is, in turn, caused by a long-term drop in wages set against a long-term productivity rise. Low wages translate into unsold wage goods, a loss for the producers of these goods, lower profitability in this sector, bankruptcies, unemployment, the spread of these difficulties to the sector producing investment goods and thus the generalisation of the crisis. Low wages, in turn, are said to have been caused by neoliberal economic policies.22 Marx had empirically invalidated this thesis already in the second volume of Capital by noticing that crises are always preceded by a period in which wages rise. But he did not elaborate on why low wages cannot be the cause of crises. The reason is the following. Divide the economy into department I producing means of production and department II producing means of consumption. Assume a wage reduction across the board. Labour’s purchasing power falls and labour cannot buy consumption goods whose price is equivalent to the wage cut. There are two borderline cases:

(1) If all the consumption goods are sold because the goods that cannot be bought by labour are bought by the capitalists, lower wages imply greater profits for the capitalists in both sectors. The ARP rises. Lower wages cannot cause the crisis.

(2) If the capitalists purchase none of the consumption goods intended to be purchased by labour (ie those goods remain unsold), department I profits from lower wages and is not affected by failed realisation because it does not produce consumption goods. Department II gains from the lower wages of its own workers what it loses from failed sales to its own workers. Its profits do not increase on this account. However, this department II suffers a loss because of lower purchases of consumption goods by the workers from department I. This loss is equivalent to capital’s higher profits due to lower wages in department I. On balance, department I gains what department II loses. The numerator of the ARP does not change. However, the denominator falls due to lower wages. The ARP rises even in this extreme case. Underconsumption does not lower the ARP.

It is sometimes objected that wage reductions cause lower sales by department II of consumption goods to department I, lower sales of means of production by department I to department II, losses by department I, and possibly a fall in the ARP. This argument overlooks the fact that the sale of consumption goods for the workers’ personal consumption is different and independent from the exchange of means of consumption for means of production. Wage cuts do not affect the quantity of the means of production exchanged for the means of consumption. The value exchanged does not change either. Only those goods incorporate more surplus labour and less necessary labour.

To summarise, wage reductions increase the average rate of profit in spite of unsold commodities. It follows that neoliberal policies based on massive wage reductions cannot have caused the present crisis.23 Underconsumption arises not because wages fall, but because wages fall while capital cannot absorb the consumption goods unsold to labour because of falling profits. Nevertheless, average profitability rises.

If falling wages cannot be the cause of the crisis, they must be a consequence of it—a countertendency, capital’s conscious policy to increase profitability by offloading the costs of the crisis onto its victims.

If lower wages increase profitability, could they not start the recovery? This is indeed the medicine prescribed by neoliberalism. However, during the crisis higher profits deriving from lower wages are mainly either set aside as reserves or channelled towards unproductive and speculative sectors.24 They are not invested in productive activities. The recovery is not threatened or held back by lower purchasing power as a result of lower wages (lower wages increase profitability) but rather by the extra profits deriving from decreased wages not translating into productive investments and thus into economic growth. The neoliberal medicine is an ineffective anti-cyclical prescription.

But the Keynesian claim that higher wages are needed to exit the crisis is not supported either. Higher wages decrease profitability. However, they increase labour’s purchasing power. Could not this greater purchasing power spur production, investment and ultimately economic growth, in Keynesian fashion? No. There are four reasons:

(1) Higher wages can increase the realisation of profits incorporated in unsold consumption goods. But given the high level of unsold products during crises, this might not spur new production.

(2) In times of crises extra wages can be used to pay off debts or they can be saved.

(3) Even disregarding these two objections above, department II (producing means of consumption) increases its sales and its profits but the extra profits deriving from higher sales in department II are nullified by higher wages in that department; the extra profits realised by department II by selling to department I’s labourers are nullified by department I’s lower profits. The numerator of the ARP is unchanged while the denominator rises. Average profitability falls. Greater sales at decreasing profitability are not the way for capital to exit the crisis.25

(4) Moreover, the recovery starts when the cause of the crisis has been reversed. If lower wages are not the cause of the crisis, higher wages cannot be the cause of the recovery. But if, as argued in the previous section, the crisis is caused by excess capital relative to the surplus value produced (ie by an increase in the organic composition of capital induced by technological innovations), the recovery can start only when sufficient capital has been destroyed. This will be addressed in the following section.

Wages are not only direct but also indirect (state expenditures for health, education, etc) and deferred (pensions). Increased indirect and deferred wages decrease profits because the more newly produced value is appropriated by the state in order to finance higher indirect and deferred wages, the less value is left for profits, independently of labour’s use of those facilities and of whether higher pensions increase labour’s consumption. This is why those on the right are for cuts in deferred and indirect wages.26 But the Keynesian response that an increase in these categories of salary increases consumption and thus profitability is wide of the mark. To repeat, capital’s predicament is not improved if more is sold at decreasing profits.

Both higher and lower wages, whatever form they take, are impotent against the crisis.

Of all the economic myths, the underconsumptionist one is the most firmly entrenched on the left. But it is also the most damaging for labour because it supports the illusion that the system can be reformed, and that redistributive measures can both avoid the crisis and reboot the economy. The logical inconsistencies of these claims are necessary to promote their ideological content. The notion of a reformable capitalism deprives labour’s struggle of its objective rationale for the supersession of this system and reduces that struggle to pure voluntarism.

Capital destruction and bubbles

If technological competition causes the tendential increase in the organic composition of the leading capitalists and thus the bankruptcy of the laggards and the crisis, the system tends towards capital’s self-destruction and neither to equilibrium and growth nor to stagnation. But what is capital destruction?

Machinery which is not used is not capital. Labour which is not exploited is equivalent to lost production. Raw material which lies unused is no capital. Buildings…which are either unused or remain unfinished, commodities which rot in warehouses—all this is destruction of capital.27

Marx is referring here to the destruction of real, ie productive, capital. If capital is a social relation of production, its destruction is the severance of that relation following the laggards’ bankruptcies, so that means of production, labour power and other commodities are prevented from acting as capital. But outside of this relation, these commodities lose both their value and their use value—they become potential capital which might be again realised capital in the next upward phase of the cycle. By the time they are employed again they might have lost a part of their use value. If they lie unused in warehouses, part or all of their use value might vanish due to the effect of time, weather, etc. If their use value is (partly) destroyed, the value contained in them is also (partly) destroyed. Wars (a consequence of crises) have the same effect. In cases in which the use value is unaffected but prices fall, the value lost by the seller is gained by the buyer.28 This is not really capital destruction but it might “act favourably upon reproduction” if the buyer is “more enterprising than [those commodities’] former owners”.29 In short, destruction of real capital is the severance of the capitalist production relation and possibly the destruction of the use value and thus of the value contained in objective commodities as a consequence of that severance.

The catalyst for the destruction of real capital is the destruction of fictitious capital, ie the severance of the debt/credit relation due to debt default. As we have seen, as profitability falls in the productive sectors, productive capital migrates to the fictitious sphere where it becomes fictitious capital. The greater the influx of capital, the higher the price of the titles of debt that form this fictitious capital. The same applies to stocks.30 As more capital expecting further price rises is drawn in, the price of the titles dealt with on the financial markets rises and the process becomes self-reinforcing. Fictitious profits rise. A speculative bubble is in the making.

Suppose a bank wants to purchase mortgage-backed securities but lacks sufficient capital. It borrows capital from other (creditor) banks. If the mortgagers default or if the bank has bought derivatives (eg collateralised debt obligations based on mortgage-backed securities) whose collateral has become worthless, the bank has on its balance sheets “assets” whose price must be drastically written down or even erased. If its equity capital is too low to absorb those losses, it might have to close down. The debtor bank’s difficulties might cause a run on the creditor banks if their depositors fear that the debtor bank could default on its debts. These creditor banks might be unable to satisfy their clients’ withdrawal demands and fail as well. If the creditor banks have bought a credit default swap from an insurance company, these bankruptcies affect the financial health of the insurance company as well. It has insured the creditor banks on the assumption that they cannot all fail at the same time, ie on the assumptions of the impossibility of a generalised financial crisis.31 In case of generalised defaults, the insurer does not have sufficient capital to pay all banks and fails as well. A default unleashes a domino effect because of the pyramid of debts.

The great increase in speculative capital rests not only on the inflow of real capital from the productive sphere but also on the ballooning of credit. The prime mover is arbitrage. Speculative funds compete for capital with other funds (eg investment funds). They must offer higher profits. To this end, an arbitrageur bets on a commodity’s price increase (goes “long” on one market to use modern finance’s silly terminology) and simultaneously bets on a different commodity’s price decrease (goes “short” on another market) or vice versa. For example, a speculator can go long on dollar-denominated bonds and short on euro-denominated bonds. They could do this by purchasing the former and selling the latter because they bet on a price rise in the former and a price decrease in the latter. If the interest rate on the US bonds falls, the price of the bonds in their possession rises and they can sell them a higher price. If the interest rate on the euro-denominated bonds rises, their price falls and the speculator, having sold them because they had bet on their price falling, can purchase the same quantity of bonds at a lower price. Since the interest rate differentials can be very small, large capitals must be invested. But speculative funds do not have sufficient money and must resort to credit. The surge of modern speculation requires an equal surge in credit.32 The same trade (in this example, long on the dollar-denominated bonds and short on the euro-denominated bonds) is carried out by hundreds of funds so that huge quantities of borrowed capital are invested in it. This is a potential speculative bubble. If prices move in the desired direction, the arbitrageurs make a profit. But if prices move in the wrong direction, losses can be generalised and huge. Since speculative funds are highly leveraged—ie they have relatively little equity of their own—the funds with the highest leverage ratio are the first to go and, furthermore, these bankruptcies cause losses for creditor financial institutions and thus affect their profitability as well, fuelling the financial crisis.33

Another feature of modern speculation is that the financial muscle of speculative funds is such that they can bet on a financially weak state’s debt (state bonds) by purchasing credit default swaps against that state’s inability to roll over its debt. This causes anxiety in international investors as to that state’s financial health, something that forces an increase in the rate paid on those bonds, a further weakening in that state’s finances (due to the payment of higher interest) and possibly of the state’s default on its debt and that currency’s devaluation. Those who had bet on this occurrence can reap enormous profits.

The chain reaction of defaults in the financial sphere ignites a similar process in the real sphere. But the productive sphere is affected by the massive destruction of fictitious capital because of the former’s already weakened profitability, which is what provoked the migration of capital to the financial and the speculative spheres and the surge of credit in the first place. The real economy is the cause of both the rise and the burst of the financial/speculative bubble. It is at this point that the real dimension of the weakness of the productive economy emerges. The deterioration of the real economy is shown in Figure 5 (below), which shows that less and less value is produced in the real economy; Figure 1, which shows that less and less value is realised relative to investment in the real economy (ie the long-term decline in the ARP); and Figure 3, which shows that profitability would be much smaller were it not for the increase in the rate of exploitation.

At present the financial bubble has reached gigantic proportions. The size of the derivatives markets (eg mortgage-backed securities, collateralised debt obligations and credit default swaps) is now ten times the world’s GDP and growing. The collapse of the bubble has been countered by massive injections of liquidity into the banking system.34 But skyrocketing governments’ debts and deficits have taken the pressure off the banking system only to create a huge state debt bubble and a looming sovereign debt crisis. By March 2011 the combined deficit of the OECD countries had grown almost sevenfold since 2007, while their debt had reached a record $43 trillion. In the eurozone deficits increased 12-fold in the same period, while debts had risen to $7.7 trillion.35 The recently agreed European Stability Mechanism (which will replace the European Financial Stability Facility that came to the aid of Greece, Ireland and Portugal) will only come into effect in 2013 and will be founded with just 500 billion euros.36 Clearly, this will only postpone the day of reckoning.

It is fashionable nowadays to try to integrate Hyman Minsky and Marx. A detailed critique of this approach is beyond the scope of this article. Here I shall mention only a couple of points. First, both for Marx and for Minsky the capitalist economy is fundamentally unstable and develops through time (whereas neoclassical theorems as well as many Marxists focus on equilibrium and abstract from time). But here the similarities end. Minsky (following Keynes) sees the economy “from the boardroom of a Wall Street investment bank”,37 Marx from the perspective of labour. Therefore, for Minsky, the economy’s instability is basically financial instability. This is due to the “subjective nature of expectations about the future course of investment”.38 Investments here are basically financial investments because they are determined by borrowing and lending. For Marx, the economy’s instability is an objective feature, the result of the crisis-prone tendency in the real economy, first in that sector and then in the financial and speculative ones. The major subjective determinant of investment and employment is the individual capitalist’s expected profit rates. But the ARP falls just because of the subjective nature of expectations, because all capitalists aim at maximising their profit rates by introducing more efficient techniques. Also, for Minsky, profits depend on expenditures whereas for Marx they depend of the rate of exploitation. More generally, Minsky erases Marx’s classes, class interests and class struggle. Thus, for Minsky, government spending (deficits) can offset private spending and even increase profits.39 For Marx, value transfers from capital to labour decrease profitability but increase labour’s consumption, while transfers from labour to capital increase profitability but augment the difficulties of realisation. Neither redistribution nor Keynesian polices can push the economy out of depression and crisis. Marx’s and Minsky’s are not complementary but radically alternative theories. And, in any case, there is nothing in Minsky concerning financial crises and bubbles that cannot be explained by applying Marx’s analysis and categories to the present.

The recovery

The crisis is preceded by a period in which the countertendencies, while unable to hold back the fall in the long-term trend of the ARP, manage to avoid the destruction of capital. This is the depression. But at a certain point the tendency towards capital destruction manifests itself in spite of the countertendencies. This is the crisis. The recovery begins when the conditions emerge for the ARP to start rising again. The boom starts when higher profitability translates into an accelerated capital accumulation. Let us then consider the conditions for the recovery to take off. Just as the economic expansion carries within itself the seeds of the crisis, so crisis is the humus that generates the recovery. A distinction should be made between the secular recovery and shorter-term recoveries. Let us begin with the latter.

(1) Labour power is available in large quantities due to unemployment. Consequently, wages are low and the rate of exploitation is high.

(2) The speculative bubble must have burst so that the unproductive sectors’ claim on the surplus value extracted in the productive sector is reduced.40

(3) Constant capital is available for new productive investments both because of large reserves created during the depression and because, following the explosion of the financial bubble, capital that had migrated to the unproductive sectors returns to productive ones.41

(4) The commodities (including the means of production) of bankrupt capitals are bought at lower prices by surviving capital. This decreases the average organic composition.

These are the conditions for an increased production of surplus value. But they are not sufficient. The extra value and surplus value must be realised. The condition for this is that sufficient capital has been destroyed, ie that sufficient capitalists have gone bankrupt: “Under all circumstances…the balance will be restored by the destruction of capital to a greater or lesser extent”.42 The capitalists who have weathered the storm can fill the markets left empty by the bankrupt capitalists or can create new markets, which replace the older ones and can attract the purchasing power previously spent on the product of the bankrupt capitals. At this point extra production gets the green light and profits are reinvested in the productive sphere, together with the reserves set aside during the crisis. Enlarged reproduction follows. Capital needs a moment of catharsis. It needs to destroy itself partially in order to regenerate itself. The larger the destruction, the more vigorous the recovery.

Consider the Keynesian alternative to Marx’s view. I have already rejected the view that pro-labour redistribution can start the recovery. The question now is whether Keynesian policies proper, based on state-induced production rather than on the redistribution of already produced surplus value, can do the trick. These policies hinge on the investment of idle reserves, of uncapitalised surplus value. In essence, the state appropriates profits (eg through taxation) or borrows them (eg by issuing state bonds) and uses them to commission public works to private capital.43 Clearly, as long as these policies are applied within capitalism, their success must be measured by their ability to increase private capital’s profitability.

The Keynesian argument holds that state-induced investments increase employment and wages. These spur the sale of consumption goods to labour, which in turn increases production and profits, thus starting the recovery. Let us examine this thesis. Let us first examine the case in which the state appropriates, rather than borrowing, a share of private capital’s reserves or profits. Let us divide private capital into two sectors: sector I producing public works commissioned by the state (schools, hospitals, roads, etc) and sector II encompassing the rest of the capitalists, ie the producers of both means of consumption and means of production needed by the capitalists in sector I.

Faced with underconsumption (the Keynesian alarm signal) the state appropriates profits (eg through taxation) from sector II to a value of S. It uses this both to pay sector I, at the going rate of profit, p, and to advance the capital sector I needs for its production of public works (S−p). Then:

(1) The state receives public works from sector I to the value of

S−p+p*, where p* is the surplus value generated in sector I (whether p* is equal to p or not). Sector I realises its profits because, having received p from the state, the surplus value generated by it during the construction of public works (p*) belongs to the state.

(2) How does the state realise S−p+p*, the total value incorporated in public works? Under capitalism value is realised only if and when it is metamorphosed into money through the sale of the use value in which it is incorporated. Since the state does not sell public works (unless it privatises them, but privatisation falls outside our present scope), it would seem that that value remains potential, trapped in an unsold use value. However, public works can realise their value in a different way. Their use value is consumed by the users of those facilities who, in exchange for this use, must pay in principle for the share of the value contained in the public works they consume. Once the public works are totally consumed, the state receives S−p+p*. The state has realised the potential value of public works by charging capital and labour for their use. These fees are an indirect reduction of wages and profits.

(3) A value p is transferred via the state from sector II to sector I. This transfer does not affect private capital’s ARP. However, sector II has lost S. The private sector loses S−p to the state.

(4) The state has gained S−p+p*, sector I has gained p, sector II has lost S, and the private sector has lost S−p. The numerator of private capital’s ARP decreases by S−p. The denominator rises because of the investment of S−p in sector I. The ARP falls on both accounts. However, employment and wages increase due to the previously idle S−p which is invested by sector I.

(5) The state could provide public services to labour either partly or completely free of charge. This increases indirect wages but cannot prevent the ARP in the private sector from falling.

Public investments not only reduce private capital’s profit rate, but also crowd out private investments and thus reduce the mass of profits that can be appropriated by the state. This deprives Keynes’s “somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investments” of a real basis.44 However, this critique is insufficient. To build public works, sector I’s capitalists (the producers of public works) purchase labour power on the labour market and means of production from sector II. Moreover, both capital and labour in sector I purchase means of consumption from sector II. Sector II might expand and thus the mass of profits it generates might increase. But sector II’s private capital expands its investments and its mass of profit only if the rate of profit expands. The conditions are: (a) Keynesian investments are large enough to absorb inventories and excess capacity so that new production can start; (b) that they can be constantly renewed; (c) that they are invested in low organic composition technologies; and (d) that their profits are reinvested in the productive sphere so that more surplus value than S−p is produced. This is highly unlikely, if not impossible. Nevertheless, let us assume that profitability increases. Might this not be the start of a new process of expanded reproduction?

As seen above, the recovery presupposes not only a greater production of surplus value percentagewise, but also the conditions for that greater production to be realised. This condition is the destruction of capital, the disappearance of the weaker capitals and thus the possibilities for the surviving capitals to step into the markets left vacant or to create new fields of investments replacing the old ones. But each time Keynesian policies manage to raise private capital$7_$_s average profitability, they at the same time prevent it from destroying itself and thus from creating the condition for its own recovery. Were it for these policies enacted, recovery would never come about.

This disposes also of the argument that Keynesian policies could be financed through borrowing and that the debt could be repaid when the recovery sets in. Keynesian economists think that this is their strongest argument. Actually, it is here that the Keynesian hypothesis is weakest. Keynesian policies not only postpone the recovery by postponing the crisis. In case of borrowing, the predicament is aggravated by the repayment by the state of the borrowed capital plus interest, something that inevitably translates into budget cuts and higher taxes. Default by the state has the same negative effects on both capital and labour. At this point, radical Keynesians argue, the state sector should not work on capitalist principles and its continuous expansion would provide a way towards a non-capitalist economy. Aside from the political naivety of this argument, it is clear that this type of policy finds its limit in the decreasing production of surplus value in the capitalist sector.

In spite of Keynesian ideology, Keynesian policies are inevitably at least co-financed by labour—through appropriation of the labourers’ savings, through the reduction of indirect and deferred wages, etc. For the sake of argument, instead of determining the conditions under which these policies raise the ARP, let us assume that they always raise it. Even in this extreme case, the magic of Keynesianism vanishes into thin air. In fact greater profitability would be at the cost of labour, contrary to the stated Keynesian aim. The secret of these policies’ success is simply a higher rate of exploitation rather than labour’s higher consumption. Greater profitability would also hinder a self-sustained recovery because these policies prevent capital self-destruction.

It is for these reasons that it is unacceptable to argue, “If the state makes available, to as many people as possible on an equal basis, the capabilities that capitalism has brought into existence, stepping in wherever private capital will not, the crisis will end”.45 On the contrary, the crisis will deepen. Shaikh too thinks that direct government investment can pull the economy out of the crisis. This would stimulate “demand provided that the people so employed do not save the income or use it to pay down debt”.46 Given that the banks need labour’s savings and that the default on debts means principally default on banks’ debt, this is a sure recipe for a financial crisis. Similarly, Foster argues, “Theoretically, any increase in government spending at this time can help soften the downturn and even contribute to the eventual restoration of economic growth”.47 These kinds of proposals have a common characteristic: they do not concern themselves with who should finance these policies. But, aside from this macroscopic defect, given that the economy exits the crisis through capital destruction, these policies delay rather than prevent the onset of the crisis. It is here that the incompatibility between Marx and Keynes emerges vividly.

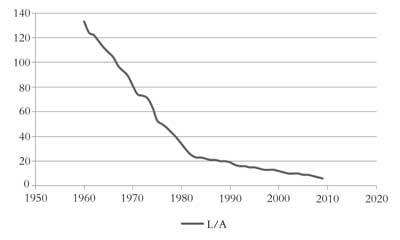

We now come to the conditions for a long-term recovery and boom. Let us first look at where we are heading. Figure 1 shows that increasingly lower profit rates are realised in the productive sectors. This is because less value and surplus value are produced in those sectors. To see this, let us calculate the reciprocal of the organic composition of capital in terms of the labour power employed rather than in terms of variable capital (money wages). We obtain a ratio for the productive sectors whose numerator is labour power and whose denominator is the assets. Call the former L and the latter A. Figure 5 shows the shape of the L/A ratio.48

In 1960, 133 workers were necessary for one unit of fixed assets. By 2009 that number had dropped to six. The new value, and thus the surplus value produced per unit of invested assets, has been falling for the past 50 years (no pre-1960 data is available). The number of workers required by the growing value of assets keeps decreasing and seems to tend towards the secular “absolute overproduction of capital”,49 the point at which extra units of capital will produce no new value.50 For the US, this spells appropriation of surplus value from other countries, through appropriation of raw materials (such as oil), through a constant deficit in the trade balance (since 1971) or by importing goods produced with low technologies and high rates of exploitation from countries such as China. But above all, as argued above, it spells the need for capital to self-destruct on a huge scale.

Figure 5: Labour units per unit of assets in the productive sector (millions of dollars), 1960-2009

Some authors argue that government civilian investments could produce a sustained economic recovery but that they have not done so because of their limited size. The example usually given is the period of the 1929 Wall Street Crash, the ensuing Second World War and the long period of prosperity that followed it. If massive state-induced investments in the arms industry have pulled the economy out of a long and deep recession and ensured a “golden age” for capital, so the argument goes, why could not the same be done in peacetime by investing in the civilian economy? Would this not be the condition for a long-term, possibly secular recovery? Empirical data readily debunk this thesis. Gross federal debt as a percentage of GDP decreased constantly during the golden age, from 121.7 percent in 1946 to 37.6 percent in 1970.51 The golden age was not due to Keynesian policies.

What, then, caused the long post-war period of prosperity? Consider the impact of the war economy. Prior to it, the ARP fell from 14 percent in 1929 to 6 percent in the depth of the recession in 1933. After that it started to recover and by 1939, just before the war, it had climbed to 11 percent. After a very short spell of war-induced high profitability, the ARP started to fall vertically. Only one year after the end of the war, in 1946 it had gone back to 14 percent, its 1929 level.52 The war effort had only a very short-lived effect on average profitability after the Second World War. Contrary to what is almost universally believed, the decline of the system began shortly after the war and not in the early 1970s even if it became apparent only in the 1970s.

Why did the war bring about such a jump in the ARP in the 1940-5 period? The first factor was a fall in the organic composition because of near full-capacity utilisation of existing means of production (rather than the production of new means of production). The denominator of the ARP not only did not rise, but dropped because the physical depreciation of the means of production was greater than new investments. At the same time, unemployment practically disappeared. Decreasing unemployment made higher wages possible.53 But higher wages did not dent profitability. In fact, the conversion of civilian into military industries reduced the supply of civilian goods. Higher wages and the limited production of consumer goods meant that labour’s purchasing power had to be greatly compressed in order to avoid inflation. This was achieved by instituting the first general income tax, discouraging consumer spending (consumer credit was prohibited) and stimulating consumer saving, principally through investment in war bonds. Consequently, labour was forced to postpone the expenditure of a sizeable portion of wages and rising wages did not affect the ARP.54 At the same time labour’s rate of exploitation increased.55 In essence, the war effort was a labour–financed massive production of means of destruction.

After the war, the economy started reconverting from military to civilian industries.56 But the technologies applied to the civilian economy were no longer the pre-war ones. They were those developed during to the war. As these technologies became increasingly capital-intensive, the organic composition started to rise. At the same time, the power of the working class had grown due to the war period near full employment. Capital started to flow into the production of consumption goods. This required the release of the purchasing power pent up during the war. Labour’s standard of living rose. This spurred the manufacturing of means of production both for means of consumption and for means of production and thus the creation of the demand for these goods.57 The multiplying reciprocal effects of high demand and productive capacity resulted in long-run expanded reproduction. But this could not continue indefinitely because the seeds of the crisis had already been sown in this boom era. Higher wages, lower exploitation and a higher organic composition meant that the ARP started to fall soon after the war (see Figure 1). The golden age was a time of great prosperity caused by the previous huge destruction of capital and of labour power. But it was also the period of incubation of the crisis that followed, as the fall in the ARP during the period shows. The widespread view that the economy started to deteriorate in the 1970s ignores the growing evidence that the ARP started to fall well before that time. This incubation, ie the progressive deterioration of profitability, was hidden by four factors: (a) capital’s higher productivity; (b) the technological leaders’ higher profitability; (c) the absorption of labour power by the expanded reproduction of the technological leaders; and (d) labour’s improved living conditions.

This led to generalised welfare, even though very unequally distributed (think of the regional, race and gender disparities). Thus, before the effects of the lower ARP could emerge, 25 years went by. At that point, the long descent of the ARP that had begun right after the war put an end to the golden age. The effects of the fall in the ARP had been merely postponed. It looked as if the new technologies had spurred the economy. Actually, far from increasing general profitability, they were the major force behind the long, secular increase in the organic composition and consequent fall in the ARP.58

But the war-related innovations also had another effect. When they started to penetrate into the civilian economy, new products came into being. New needs had to be created. The material basis of capitalism began to undergo a profound mutation. The post-war capitalist society changed beyond recognition while the fundamental laws of its motion remained unchanged.

The golden age lasted until around 1970. Around that year the movement changed direction. The rising organic composition started to bite into employment. The rate of unemployment rose from 4.9 percent in 1970 to 10 percent in 2010 according to the U3 measure (but 17 percent according to the U6 measure and 22 percent according to SGS estimates). High unemployment affected the rate of exploitation, which rose enormously especially with the advent of neoliberalism (see Figure 2 above). The condition of the working class began to deteriorate and has been worsening ever since.

Can the above be a guide for an anti-crisis policy in peace times? The translation of the post-war experience to peace times suggests that massive and increasing quantities of value would have to be invested not in the production of wage goods (something that would require a greater production of those goods, higher wages and lower profits) but in the production of wasteful or luxury goods (because their realisation does not require higher wages) or without use value, ie useless articles. Higher wages could be paid but the absence of wage goods would require an increasingly pent-up purchasing power which would have to be forcibly channelled towards consumer savings in order to avoid inflation. Moreover, higher profitability would require that the growing quantity of new value would be invested in low-technology, low organic composition techniques. All this is obviously absurd and in any case could only be done for a few years as during the Second World War. It would be unsustainable as a long-term or permanent solution. Alternatively, massive civilian investments could be labour-financed, based on low wages and high rates of exploitation (in order not to dent profits) but not directed towards the production of wage goods. This is not what the golden age was about. A return to the golden age within the context of this secular decline in profitability is impossible.

What next? Forecasting is notoriously difficult. Another world conflagration is a possibility that cannot be ruled out. A new golden age would first require a destruction of capital even greater than that of the Second World War. Right now the only power that seems to be set to challenge the US seems to be China. But China does not have the military muscle needed to defend its interests. If and when its economic and military power threatens the US, a military confrontation will be inevitable. But this is not a proximate possibility. Lacking a gigantic conflagration, the solution to the secular fall in profitability will be economic, not military. The above has submitted that the conditions for the renewed production of increasing quantities of surplus value are already present and that what is needed is a generalised and massive destruction of capital. This destruction of capital as a social relation is inevitable because as Figure 5 shows the technologies incorporated in productive assets are increasingly approaching their limit in terms of the production of new value. The increase in the organic composition cannot go on forever. Commentators, both Marxist and otherwise, stress the danger for the system coming from runaway debt in all its forms. This is correct, but it is only half of the story. Marxist theory goes further than the analysis of financial and speculative capital. The other, determining half of the picture is that new technologies, in the process of constantly reducing variable capital in the productive sectors, are exhausting their propelling function. When they will reach their economic limit, ie when the destruction of real capital is powerless to start the economy anew on the basis of these techniques and thus of their too limited employment of labour power, economic catastrophe will be inevitable.

But this will mark at the same time a new phase of capital accumulation on the basis of a massive wave of investment in new technologies. This is what happened after the Second World War. That war proved to be a mine of inventions, from the jet plane to ballistic missiles, from atomic energy to computers, from synthetic rubber to radar, just to mention a few. These inventions became the new technologies that flowed over into the civilian economy and became the new material basis of the post-war economy. They replaced old fields of investment and means of production and formed new ones (the need for whose commodities had to be created). Furthermore, old lines of production were completely revolutionised. The civilian economy was jump-started again on a new material basis.59

But that was 65 years ago. If the productive sector of the US economy is anything to go by, existing technologies or new developments on the basis of these technologies are tending towards the point at which capital increments will produce a minimal new value or no new value at all (as Figure 5 shows). What capital now needs is the application of radically different technologies that will create new commodities and new needs on a massive scale on the basis of an initial low organic composition.60 New technologies have been developed towards the end of the previous century and are available and ready for large-scale application across the entire spectrum of the economy when the economic conditions are ripe. Let us mention some of them: biotechnology, genetic engineering, nanotechnology (the attempt to control matter on a molecular scale); bioinformatics (the application of information technology and computer science to the field of molecular biology); genomics (the determination of the entire DNA sequence of organisms); biopharmacology (the study of drugs produced using biotechnology); molecular computing (computational schemes which use individual atoms or molecules as a means of solving computational problems); and biomimetics (the science of copying life, ie the transfer of ideas from biology to technology).61

We seem to be approaching a new phase of the development of capital’s productive forces, based on completely new technologies. These new technologies and sciences might even (partly) solve the problems created by the existing ones; they might find alternatives to oil as the basic but depleting source of energy and might halt the destruction of our natural habitat, possibly creating an alternative, artificial one. But, on the basis of the history of capitalism, it is safe to speculate that this new phase, far from delivering a new era of civilisation, might improve the condition of a minority of labour (whose characteristic will be undoubtedly changed by capitalism’s new material basis) but at the same time will generate new and even more terrible forms of exploitation. This, of course, under the assumption that capitalism will avoid a major ecological catastrophe and/or a new world conflagration, which would threaten the survival of humankind, unfortunately an increasingly unrealistic assumption. On this account too, humanity’s only hope is a radical social restructuring following a communist revolution.

Marx or Keynes?

But let us return to the present. Keynesianism holds that “austerity” measures hinder economic growth and thus the repayment of the state debt by compressing internal demand. However, lower wages increase profits, a necessary even if not sufficient condition for recovery. Economic growth and thus debt repayment are hindered not by lower wages but under crisis conditions (ie as long as sufficient capital is not destroyed) by capital investing these higher profits in the speculative and financial sectors rather than in the productive one. The struggle for higher wages, greater employment and better living and working conditions can be waged from two opposite perspectives. From the underconsumptionist and Keynesian perspective, this struggle not only improves wages, employment and the living conditions of the working class. It also provides the way out of the crisis and of state debt by improving profitability and fostering growth through the labourers’ greater purchasing power. This thesis stresses the commonality of interests between capital and labour. The Marxist thesis too argues that those demands are sacrosanct. But this struggle is waged from the perspective of the contradictory and mutually exclusive interests of the two fundamental classes. Labour should fight for a more favourable redistribution of the value it itself creates, for state-induced civilian investments and in general for labour-friendly reforms, knowing that labour’s gains are capital’s losses and thus contribute to the objective weakening of capitalism rather than to its strengthening. This struggle should involve a whole series of demands (including the defence of our ecological heritage and the reconversion of the military industry) whose purpose is in the short term to make the culprits and not the victims pay for the effects of the crisis and in the longer term to foster the consciousness that the way out of the crisis is the way out of this system. For those who are interested in ending this barbarous social system, the choice is clear: Marx or Keynes.

Appendix: statistical sources

Profit rate: The profit rate is computed for the productive sectors at historic costs. The best approximation for these sectors is the goods-producing industries. These are defined as agriculture, mining, utilities, construction and manufacturing. However, in this paper utilities are disregarded (see below). Given that statistics are not presented according to the categories of Marxist analysis, the data on the profit rate is at best an approximation to its real value. However, the movement and trend are reliable indications because the data is, theoretically, consistent through time.

Profits: Profits are from Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) tables 6.17A, 6.17B, 6.17C, 6.17D: “Corporate Profits before Tax by Industry” (billions of dollars). In the first three tables utilities are listed apart, but in table 6.17D they are listed together with and cannot be separated from transportation. I have decided to disregard utilities in all five figures.

Fixed assets: Their definition is “equipment, software, and structures, including owner-occupied housing”.62 The data considered in this paper covers agriculture, mining, construction and manufacturing (but not utilities—see above). Fixed assets are obtained from BEA, Table 3.3ES: “Historical-Cost Net Stock of Private Fixed Assets by Industry” (billions of dollars; year-end estimates).

Wages: Wages for goods-producing industries are obtained from BEA, table 2.2A and 2.2B: “Wages and salaries disbursements by industry”

(billions of dollars).

Employment in goods–producing industries: This is obtained from US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, series ID CES0600000001.

Notes

1: An extended version of many of the arguments in this paper can be found in Carchedi, 2011. For a useful review of contemporary Marxist theories of crises, see Choonara, 2009.

2: Anwar Shaikh writes in a recent article, “Marx argues that it is the difference between the two rates [rate of profit and rate of interest], which he calls the rate of profit-of-enterprise, that drives active investment. Keynes says much the same thing”-Shaikh, 2011, p46. Actually Marx says no such thing. For Marx, “active investment” is basically moved by competition, by the need to keep technologically abreast of competitors, as Shaikh should know.

3: Marx, 1967a, p240. That only labour (under capitalist production relations) can create (surplus) value is one of the basic tenets of the labour theory of value. The reasons for accepting this theory are that it is (1) consistent, (2) the only theory fit to defend labour’s cause against capital and (3) empirically substantiated. Empirical substantiation is provided by figures 1 and 4 below, which show that the ARP is inversely related to the organic composition of capital and thus directly related to the labour power employed. Thus these charts dispose of the thesis that value is created by machines or by both machines and labourers.

4: Statistical sources and methodology are listed in the appendix to this paper. For recent and differing ways to calculate the profit rate, see Kliman, 2010; Freeman, 2010; Roberts, 2009; Moseley, 2009; Shaikh, 2011; Husson, 2010; Giussani, 2005; Wolff, 2003; Ekonomakis and others, 2010; and Cockshott and Zachariah, 2010.

5: Tendency and countertendencies are made empirically visible by their trends.

6: Husson, 2010.

7: Kliman, 2010; Freeman, 2010.

8: For example, Husson, 2010, p8. But the critics along these lines are legion.

9: Quoted in Brenner and Probsting, 2008, p66.

10: Since the data on wages includes managerial income and that of all those who in Marx’s theory perform the work of control and surveillance (Carchedi, 1977, chapter 1), and since this income derives from surplus value, a more accurate measurement of wages along these lines would produce a higher rate of exploitation. Wolff, 2010, reaches similar conclusions by focusing on manufacturing.

11: In a curious reversal of positions, while some Marxists deny that the increase in the ARP has been due to higher exploitation rates, JP Morgan, one of the world’s major banks, writes that “profit margins have reached levels not seen in decades” and that “reductions in wages and benefits explain the majority of the net improvement in margins”-JP Morgan, 2011.

12: National Employment Law Project, 2011.

13: See, for example, Husson, 2010, p13; Chesnais, 2009, p11; Cockshott and Zachariah, 2010.

14: Husson argues that financial profits should be included in the computation of the average profit rate because they are “a component of GDP of which the real counterparts are consumption, investment and the trade balance”-Husson, 2010, p2.

15: Marx, 1967b, p470.

16: Marx, 1967b, p390.

17: Marx referred to capitalisation as “the formation of fictitious capital”-Marx, 1967b, p466. This is the formation of the price of capital that is fictitious because it represents debt. On the other hand, Perelman (2008, p19) and many other commentators consider capital as fictitious because its price is given by the capitalisation of future incomes.

18: Carchedi, 2011, chapter 3, deals extensively with this topic. For a clear numerical example involving collateralised debt obligations, see Saber, 2010.

19: Pension funds’ investment in private financial capital (of which Figure 4 is an example) transforms them into profit-seeking financial and speculative institutions as well as in pools of liquidity for capital’s reproduction. The workers are thus exposed to the loss of their pensions, as in the 2007-9 financial crisis. For a well-written account of this process in Iceland, see Macheda, 2011, especially section 4.

20: Saber, 1999.

21: Saber, 1999, p106.

22: If the current crisis is caused by this policy, other crises must have had other causes. For example, Anne Davies (2010, pp419-420) speaks of a “variety of possible contradictions” causing the crisis, “such as…a falling profit rate or a realisation problem”. However, if crises are recurrent, the question is what compels all those causes to recur. One cannot escape the question as to the ultimate cause of crises. See Carchedi, 2010.

23: This should not be construed as saying that rising wages were the origin of the crises either (the profit squeeze thesis). See Carchedi, 2010.

24: “The current members of the S&P 500 are sitting on about $800 billion in cash and cash equivalents, the most ever”-Melloy, 2011. By August 2011, estimates had risen to around $1 trillion-Valsania, 2011; Krauth, 2011.

25: For Foster and Magdoff (2008), “The best way to help both the economy and those at the bottom is to address the needs of the latter directly.” This helps labour, not the (capitalist) economy whose index of health is the profit rate rather than labour’s consumption.

26: In the US in the 1950s the share of income tax collected from corporations was 39 percent and individuals’ share was 61 percent. In the 2000-9 period the percentages were respectively 19 percent and 81 percent. At the same time, 20 percent of the US budget went towards the military-Links, 2011.

27: Marx, 1971, p495.

28: The depreciation of some means of production due to the introduction of new and more productive ones is not destruction of capital because the former create more surplus value but less use value than the latter and thus lose part of their surplus value to the latter.

29: Marx, 1971, p495.

30: The question as to whether stocks are titles of ownership or of debt is a contentious one. For the present purposes, they are equated to bonds.

31: The famous Black-Scholes model for the valuation of derivatives is based on a set of assumptions, one of which is that there is no counterparty default risk, ie on the absence of crises (Saber, 1999, p35). In the light of the collapse of the US mortgage-backed securities (Carchedi, 2011, chapter 3), this model is one more testimony to the monumental irrelevance of academic economics.

32: These aspects are dealt with in detail in Saber, 1999.

33: The similarity between productive and speculative capital is that they both tend towards self-destruction and in principle the first units to fail are the weakest. In the productive sectors they are the technologically backward capitals; in the speculative sectors they are the most highly leveraged.

34: $10 trillion, according to John Bellamy Foster in March 2009-Foster, 2009.

35: Spiegel Online International, 2010.

36: Spiegel Online International, 2011.

37: Minsky, 1982, p61.

38: Minsky, 1982, p65.

39: Minsky, 1982, pp64-65.

40: “Banks have written off about $2-3 trillion out of debt assets of around $60 trillion globally, so less than 5 percent. They still hold trillions of debt that represent worthless assets. Before profitability can really be restored, much more of this fake value needs to be destroyed”-Roberts, 2009, p285.

41: Basically, large investors sell shares in financial and speculative firms and buy (possibly newly issued) shares in industrial firms.

42: Marx, 1992, p328.

43: Direct investment by the state, rather than through private capital, would introduce significant changes but would not alter the essence of the argument. Military Keynesianism and green Keynesianism are not dealt with here for lack of space. See Wolff, 2010; Foster, 2009.

44: Keynes, 1964, p378.

45: Freeman, 2009.

46: Shaikh, 2011, p57.

47: Foster, 2009.