The United States is caught up in the most serious financial crisis since the Great Depression.1 This crisis calls into question the stability and indeed the very survival of capitalism. Unlike the savings and loan crisis 20 years ago, which was confined to a single industry, or the Asian currency crisis ten years ago, which was mostly confined to less developed and developing countries, the present crisis affects financial markets generally and emanates from the major centre of capitalism. It thus threatens to become a global crisis. And a major financial crisis cannot fail to have serious repercussions in the “real” (non-financial) economy—production, employment, trade in goods and services, and so on.

Because Marxists are famous for “predicting five out of the last three recessions”, I need to point out two things before continuing. First, the term crisis does not mean collapse, nor does it mean slump (recession, depression, downturn). A crisis is a rupture or disruption in the network of relationships that keep the economy operating in the normal way. Whether or not it triggers a collapse or even a slump depends upon what happens next.

The US economy is not currently on the verge of collapse, and it is far too early to predict a collapse. By papering over bad debt with still more debt, policymakers have repeatedly been able to pull the national and world economies through earlier crises, and this strategy may well work again. And while the US is probably in the midst of a recession, the downturn has been—thus far—a relatively mild and uneven one. For instance, payroll employment has fallen seven months in a row (through to July), but the total decline is less than half the decline that occurred during the first seven months of the last recession, in 2001, which itself was relatively mild.

Second, although my perspective on the crisis is perhaps not yet the majority view, it is increasingly becoming mainstream. In April, Yale University financial economist Robert J Shiller suggested that the crisis reveals “the fundamental instability of our system”.2 Just prior to the US government’s announcement of a plan to rescue the giant mortgage lending firms Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, business columnist Ambrose Evans-Pritchard wrote, “The meltdown at the[se] two federally chartered agencies amounts to a heart attack at the core of the US credit system, leaving it obvious that the Bush administration has failed to stabilise the financial system”.3 George Soros told the Reuters news agency two days later that we are in the midst of “the most serious financial crisis of our lifetime”. “It is inevitable that it is affecting the real economy”.4 Alan Blinder, a Princeton University economist and former vice-chair of the US Federal Reserve, told the New York Times, “We haven’t seen this kind of travail in the financial markets since the 1930s”.5

Nearly six weeks after the government rescue plan for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac was announced, Bill Seidman, former chair of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, warned that these firms could still fail, which “could cause total panic in the global financial system”. If the market is left alone to sort the problem out, “that could mean the end of the market and the financial institutions and banks”.6 Kenneth Rogoff, a Harvard University economist and former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, said that “the financial crisis is at the halfway point, perhaps”, and that “the worst is yet to come”. He also warned that one or more of the country’s biggest commercial or investment banks may fail within the next few months.7

A new manifestation of state-capitalism

The present crisis is above all a crisis of confidence. To understand what this means we need to reflect on the fact that capitalism relies on credit, and the fact that the credit system is based on promises and faith. Before potential lenders will actually lend they must be promised that the monies they throw into the market in order to get a return will in fact return to them; and they must have faith (or confidence) that these promises will be honoured. So if lenders’ faith in the future is shaken, the system’s ability to keep going from today to tomorrow is disrupted. If their faith in the future is shaken as profoundly as it has been recently, the result is a crisis that calls into question the very ability of the financial system, and therefore also the “real” economy, to continue functioning.

The Federal Reserve, the US Treasury Department and the rest of the government are acutely aware of and afraid of this crisis of confidence. As Paul Krugman, a Princeton University economist and New York Times columnist, remarked in mid-March, “[government] officials—rightly—aren’t willing to run the risk that losses on bad loans will cripple the financial system and take the real economy down with it”.8

And so, with the takeover of Bear Stearns in mid-March, and what is widely recognised as the effective nationalisation of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in mid-July,9 we are witnessing a new manifestation of state-capitalism. It isn’t the state-capitalism of the former USSR, characterised by central “planning” and the dominance of state property; it is state-capitalism in the sense in which Raya Dunayevskaya used the term to refer to a new global stage of capitalism, characterised by permanent state intervention, that arose in the 1930s with the New Deal and similar policy regimes.10 The purpose of the New Deal, just like the purpose of the latest government interventions, was to save the capitalist system from itself.

Because many liberal and left commentators choose to focus on the distributional implications of these interventions—who will the government rescue, rich investors and lenders or average homeowners facing foreclosure?—let me stress that I mean “save the capitalist system” in the literal sense. The purpose of these interventions is not to make the rich richer, or even to protect their wealth, but to save the system as such.

Consider the takeover of Bear Stearns, which was Wall Street’s fifth largest firm. On 16 March the Fed attempted to sell it off to JP Morgan Chase for the fire-sale price of $2 per share, a tiny fraction of what its assets were worth on the open market and one fifth of the ultimate sale price. Bear Stearns was in serious trouble but there were other ways of dealing with it. Had it been able to borrow at the Fed’s “discount window”, Bear Stearns could have survived the crisis it faced, which was due to a temporary lack of cash. But the Fed waited until the following day to announce that it would now open the discount window to Wall Street firms. Alternatively, if Bear Stearns had been allowed to file for bankruptcy, it could have continued to operate, and its owners’ shares of stock would not have been acquired at a fraction of their market value. Instead the Fed forced it to be sold off.

Thus the takeover was definitely not a way of bailing out Bear Stearns’ owners. Nor was the Fed out to enrich the owners of JP Morgan Chase. (The Fed selected it as the new owner of Bear Stearns’ assets because it was the only financial firm big enough to buy them.) Instead the Fed acted as it did in order to send a clear signal to the financial world that the US government would do whatever it could to prevent the failure of any institution that is “too big to fail”, because such a failure could set off a domino effect triggering a panicky withdrawal of funds large enough to bring the financial system crashing down.

The takeover of Bear Stearns was a big deal, but the government’s plan that effectively nationalises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac is a far bigger deal. These firms own or guarantee about half of all US mortgages, and they are now making or guaranteeing about three quarters of new home loans. In late April, when the spotlight was still on the Bear Stearns takeover, I called attention to:

what might prove to be far more important, because of its potential size and scope…a subtle government action taken three days later with respect to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac… On 19 March the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight [OFHEO], the regulatory authority in charge of these mortgage pools, suddenly announced that they may reduce by one third the funds they hold as a cushion against losses, and that it “will consider further reductions in the future”. This is the opposite of what one would normally expect. Because of the huge increase in mortgage loans that have gone bad, Freddie Mac in particular faces large and unexpected losses. So what it needs is a bigger, not smaller, cushion against these losses…

By telling these mortgage pools to be less prudent, not more prudent, at a time when more prudence is called for, [OFHEO] was sending a signal that the government is there to bail them out (take over their losses) if and when they go broke. Although this signal was subtle, it was understood by “those in the know”. For instance, writing on prudentbear.com, Doug Noland referred to the action as the “Nationalisation of US mortgages”.11

Two and a half months later the moment for subtlety had come and gone. The share prices of both Fannie and Freddie plummeted by almost half during the second week of July. Until that point many observers thought that the Bear Stearns takeover had provided the financial markets with sufficient assurance that the US government was ready and willing to do whatever needed to be done to prop up the financial system. But the decline in Fannie and Freddie’s share prices triggered renewed fears of the system’s collapse. Wall Street executives and foreign central bankers warned the government that “any further erosion of confidence could have a cascading effect around the world”.12

So the Treasury Department and the Fed hastily cobbled together a rescue plan over the weekend. And in a highly unusual move, Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson rushed to publicise it on Sunday (13 July), before the financial markets had an opportunity to resume activity and further damage confidence.

The rescue plan gave the Treasury unlimited authority—a “blank cheque”—to borrow whatever funds are needed to cover Fannie and Freddie’s losses. The government’s motivation is not to prop up these firms’ share prices (after the rescue plan was announced, their share prices recovered some of the ground they had lost, but they have since fallen to new lows). Nor is the government trying to bail out the shareholders. The details of the plan have apparently not been fully worked out yet, but it seems extremely unlikely that Fannie and Freddie’s shareholders will receive any money from the government. Only the institutions and investors that bought the securities they issued will be compensated, and perhaps some of them—the holders of risky subordinated debt—will also take a hit. Just as in the Bear Stearns case, the point of the intervention is to restore confidence in the financial system by assuring lenders that, if all else fails, the US government will be there to pay back the monies that are owed to them.

The new manifestation of state-capitalism we are witnessing is essentially non-ideological in character. To be sure, some movement away from “free-market” capitalism and back to greater regulation is taking place, but this is a pragmatic matter rather than an ideological one. Given the severity of the current crisis there is an extremely broad consensus, extending even into much of the US left, that the government should do whatever is needed to prevent a collapse of the financial system. If this requires that the government assume the debts of Wall Street firms, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and whatever may happen to be the next institutions that are “too big to fail”, so be it. But since the government is now committed to propping up these institutions, these institutions are ultimately gambling with public money. So there is an equally broad consensus that greater regulation is necessary in order to prevent government guarantees from giving these institutions a green light to invest and lend in an even riskier fashion than they have done to date.

It is far too soon to tell how much the government will eventually have to borrow in order to cover financial sector losses. A lot depends on how deeply the housing market declines and how much the financial crisis spills over into the “real” economy. Whatever the amount proves to be in the end, it will be ultimately paid by US taxpayers in the form of interest payments on the extra funds the Treasury will borrow. This does not mean, however, that the working class will ultimately foot the bill. Under capitalism workers’ after-tax earnings are ultimately governed by economic laws that higher taxes do not suspend.13 Thus if the taxes they pay increase, their pre-tax incomes are likely to increase as well, all else being equal, and employers are likely to be the ones who bear the ultimate burden of the tax increase. But this will cut into employers’ profits and thus retard investment, economic growth and job creation for some time to come—perhaps even decades if the mortgage losses turn out to be large and the government borrows for the long term. In this way and in this sense, then, working people will indeed ultimately bear the burden of the mortgage losses.

Of course, millions of them have already been hurt more directly, by losing their homes or by losing their equity in their homes as home prices have plummeted. Millions more are likely to be hurt in the future. Delinquency rates, the proportion of those falling behind on payments, have been rising on mortgage loans of all kinds—not only subprime loans. Between April 2007 and April 2008 the delinquency rate on prime loans (the usual type) doubled, while the delinquency rate on “alt-A” loans, which stand midway between prime and subprime varieties, quadrupled.14

The loss of home equity is especially significant because ownership of a part or all of their homes is the main way in which working people hold what little savings they have, and because their ability to borrow depends heavily upon the equity in their homes that they can offer as collateral. Negative equity—a situation in which the homeowner’s outstanding mortgage is more than his or her home is currently worth—is a particular problem. People with negative equity cannot borrow against their homes at all. But the more home prices fall, the greater the negative equity. One internet provider of housing valuations, zillow.com, recently estimated that 29 percent of homeowners who bought their homes within the past five years, and 45 percent of those who bought their homes at the 2006 peak of the housing market, are saddled with negative equity.15

Roots of the crisis

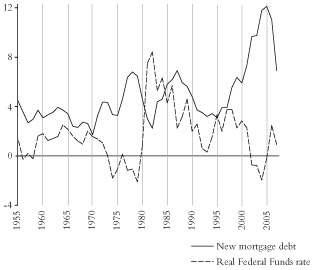

The financial crisis has its roots in the US housing sector bubble that formed earlier in the decade. Paradoxically, the bubble is largely attributable to the weakness of the country’s economy during this decade. First stock prices plunged sharply as the “dot.com” stock market bubble burst. For instance, the S&P 500 index fell by nearly half in the three years following March 2000. Then the economy went into recession in March 2001, and it was weakened further by the 9/11 attacks later that year. In order to allay the fears of financial collapse that followed the attacks the Fed lowered short-term interest rates. Although the recession was later “officially” declared to have ended in November of 2001, employment kept falling during the middle of 2003. So the Fed kept lowering short-term lending rates. For three full years, starting in October of 2002, the real (ie inflation-adjusted) federal funds rate was actually negative (see figure 1). This allowed banks to borrow funds from other banks, lend them out, and then pay back less than they had borrowed once inflation was taken into account.

Figure 1: New mortgage debt as percent of after-tax personal income and real Federal Funds rate (US)

Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis; Federal Reserve; Bureau of Labor Statistics

By trying to keep the system afloat through this “cheap money, easy credit” strategy, the Fed created a new bubble. With stock prices having recently collapsed, this time the flood of money flowed at first largely into the housing market. Expressed as a percentage of after-tax income home mortgage borrowing more than doubled from 2000 to 2005, rising to levels far in excess of those seen previously. Loan funds were so ready to hand that working class people whose applications for mortgage loans would normally have been rejected were now able to obtain them. And lenders extended what became known as “liar loans”, looking the other way when applicants for mortgages lied about their assets and incomes.

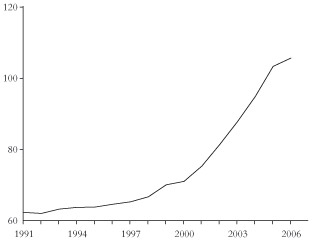

As Figure 1 shows, the trajectory of the mortgage borrowing to income ratio during the 2000-4 period is an almost perfect mirror image of the trajectory of the real federal funds rate. This is a clear indication of the close link between the explosion of mortgage borrowing and the easy credit conditions. And with new borrowing increasing so rapidly the ratio of outstanding mortgage debt to after-tax income, which had risen only modestly during the 1990s, jumped from 71 percent in 2000 to 103 percent in 2005 (see figure 2).16

Figure 2: Home mortgage debt as percent of after-tax personal income (US)

Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis; Federal Reserve

The additional money flooding the housing market in turn caused home prices to skyrocket. Indeed, total mortgage debt and home prices (as measured by the Case-Shiller Home Price Index) rose at almost exactly the same rates between start of 2000 and the end of 2005—100 percent and 102 percent, respectively.

Those of us who attempt, following Marx, to understand capitalism’s economic crises as disturbances rooted in its system of production—value production—always face the problem that the market and production are not linked in a simple cause and effect manner. As a general rule, it is not the case that an event within the sphere of production causes an event that takes place in the market, such as an economic crisis. Instead what occurs in the sphere of production conditions and sets limits to what occurs in the market. And it is indisputable that, in this sense, the US housing crisis has its roots in the system of production. The increases in home prices were far in excess of the flow of value from new production that alone could guarantee repayment of the mortgages in the long run. The new value created in production is ultimately the sole source of all income—including homeowners’ wages, salaries and other income—and therefore it is the sole basis upon which the repayment of mortgages ultimately rests.

But from 2000 to 2005 after-tax income (not adjusted for inflation) rose just 34.7 percent, barely one third of the increase in home prices. This is precisely why the real-estate bubble proved to be a bubble. A rise in asset prices or expansion of credit is never excessive in itself. It is excessive only in relation to the underlying flow of value. Non-Marxist economists and financial analysts may use different language to describe these relationships, but they do not dispute them. Indeed, it is commonplace to assess whether homes are over or under-priced by looking at whether their prices are high or low in relation to the underlying flow of income.

In retrospect, it may seem surprising that the sharp rise in home prices was not generally recognised at the time to be a bubble. But that is the case with every bubble. And some players in the mortgage market did realise that something was amiss but nonetheless sought to quickly reap lush profits and then protect themselves before the day of reckoning arrived. Moreover, there was a good reason (or what seemed at the time to be a good reason) why others failed to perceive that the boom times were unsustainable: home prices in the US had never fallen on a national level, at least not since the Great Depression.

So it was “natural” to assume that home prices would keep rising. This assumption served to allay misgivings over the fact that a lot of money was being lent out to homeowners who were less than creditworthy, and in the form of risky subprime mortgages. Had home prices continued to go up, homeowners who had trouble making mortgage payments would have been able to get the additional funds they needed by borrowing against the increase in the value of their homes, and the crisis would have been averted.

Even if home prices had levelled off or fallen only slightly, there probably would have been no crisis. In the light of the historical record the bond-rating agencies assumed, as their worst case scenario, that home prices would dip by a few percent. It was because of this assumption that they gave high ratings to a huge amount of pooled and repackaged mortgage debt (mortgage backed securities) that included subprime mortgages and the like. Today these securities are called “toxic”—very few investors are willing to touch them. But if the bond-rating agencies had been right about the worst case scenario, the investors who thought that they were buying safe, investment grade securities would indeed have reaped a decent profit.

As we now know, however, the bond-raters were wrong, massively wrong, and thus there is a massive mortgage market crisis. According to the latest Case-Shiller Index figures, between the peak in July 2006 and May of this year US home prices fell by 18.4 percent. The decline is accelerating—three quarters of it has occurred since August of 2007—and eight of the 20 metropolitan areas included in the index have already experienced declines of over 25 percent.

Along with the collapse of the housing bubble came an unexpected decline in the values of a whole gamut of mortgage backed securities, which were regarded as safe investments when the worst case scenario that was envisioned was for home prices to dip slightly.

But the crisis in the housing sector is not the sole cause of the financial crisis. Another factor is that the flow of cash from mortgage payments was packaged and repackaged as various kinds of derivatives. This made it nearly impossible to identify which mortgage loans were underlying these securities. But their value depends on whether the underlying loans are still likely to be repaid or not, so potential buyers of these securities do not actually know what the sellers are offering them. Former Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill recently compared this to ten bottles of water, one of which contains poison. If you buy one, it is very likely that you are buying safe water, but who would take the chance?17

So, although the vast majority of the outstanding mortgage loans are likely to be repaid, potential investors became unwilling to take a chance. Thus the market for mortgage backed securities became “frozen”, which impeded the ability of firms throughout a wide swath of the system to get the short-term cash they need to meet their obligations. This spring the government was forced to intervene in order to get the cash circulating again. At the time these moves, together with the Bear Stearns takeover, were widely regarded as sufficient to restore confidence in the US financial system. But the fear that surrounded the decline in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s share prices a few months later shows that the loss of confidence is more deeply rooted than had been thought.

What’s next?

Although the current recession in the US economy has thus far been relatively mild, this situation could change quickly. The credit crunch seems to have begun in earnest only since April, and one-time tax rebate cheques issued shortly thereafter have thus far served to mask its effect. A boost in export spending during the last year has also propped up the US economy, but now that recession conditions have recently spread throughout Europe, foreign demand for US made products is likely to decline.

Any new manifestation of crisis in the financial sector is sure to lengthen and deepen the recession, and the longer and deeper the recession, the greater the chances of additional financial crises. A great deal depends on how much and how long home prices keep falling. Some forecasters think they have come close to hitting bottom. But the futures market based on the Case-Shiller Index is signalling an eventual decline of 33 percent, nearly double the decline to date. And financial analyst Meredith Whitney—who has become something of a “star” since she predicted (or went public with?) Citigroup’s financial difficulties well in advance of the pack—forecasts that home prices will fall by about 40 percent. She argues that a 33 percent fall would only roll back home prices to the levels of 2002-3, but that they will have to fall further, since the rate of home ownership has since declined and mortgage loans on easy terms are no longer readily available.18

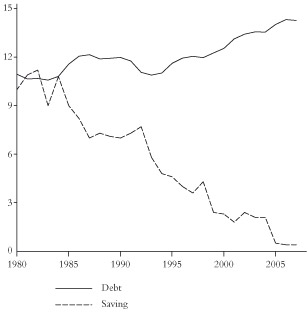

Another factor that threatens to exacerbate the economic downturn is the bursting of what Fortune magazine editor Geoff Colvin recently termed “the standard of living bubble”.19 For more than 20 years personal saving in the US has consistently fallen as a share of after-tax income. During the past three years consumers saved almost nothing (see figure 3). They have been able to save less because they have borrowed more. And until recently they often treated increases in the prices of their homes and shares of stock as a kind of saving. But with a credit crunch under way, and home and share prices both about 20 percent below their peaks, it looks as though US consumers will finally have to live within their means and try to set aside some real money for the future. Such measures could cause consumer spending to be significantly depressed for some time to come.

Figure 3: Household debt service (required payments on mortgage and consumer debt) and personal saving as a percent of after-tax income (US)

Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis (NIPA data); Federal Reserve

The Fed and other government authorities have already had to intervene repeatedly in order to try to restore confidence in the financial system. Each time their intervention has succeeded—but only until the next eruption of the crisis of confidence. If one or more giant banks or investment houses fail, as Kenneth Rogoff has predicted, or if the financial crisis worsens in some other way, the government may not be able easily to borrow the funds it needs in order to make good on lenders’ losses and thereby restore confidence. Eventually prospective lenders will question whether the US economy is strong enough for the government to meet its obligations. Or will it have to resort to paying lenders back by putting new money into circulation in excess of the new value that is created in production—in other words, to paying them back with Monopoly money? The US government can restore faith in the capitalist system only insofar as there is faith in the US government.

There are some signs that this faith is eroding. TJ Marta, a fixed income analyst at the Royal Bank of Canada’s RBC Capital Markets, recently stated, “Anytime a person or a company or a country has excessive debt, they are considered a worse credit risk. Global investors remain very concerned about the US social security problem, the US shortfall in Medicare funding, the expenses for military operations and now they are hearing that the government might have to bail out the housing market. We are on the edge of a very bad crisis here”.20 Peter Schiff, head of EuroPacific Capital, a Connecticut-based brokerage that specialises in overseas investments, said that “America’s ‘AAA’ [bond] rating has become a joke. I believe that the losses from Fannie and Freddie alone could reach $500 billion to $1 trillion. The US government will not be able to meet repayments on its debt once interest rates rise”.21

The US government’s recent state capitalist interventions are perhaps best described as the latest phase of what Marx called “the abolition of the capitalist mode of production within the capitalist mode of production itself”.22 There is nothing private about the system any more except the titles to property. As the takeover of Bear Stearns and the rescue of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac show, the government is not even intervening on behalf of private interests: it is intervening on behalf of the system itself. Such total alienation of an economic system from human interests of any sort is a clear sign that it needs to perish and make way for a higher social order.

The mainstream left in the United States no longer seriously believe this is possible, and so it has very little to say about the current crisis. For them, the only real alternatives are, on the one hand, the present system, on the other, economic chaos and disintegration. Thus their best option is to quietly become part of the new pragmatic Washington consensus. A recent editorial in The Nation, perhaps the biggest and most respected mainstream left publication, provides a striking example of this attitude. The editorial, entitled “For A New Economics”,23 lists problems including foreclosures, the credit crunch and job cuts. But the solutions given are “energy independence”, “infrastructure programmes”, investment in “job creation”, and “health and retirement guarantees”—The Nation has nothing to say about how to get out of the crisis or how to keep it from happening again.

The current economic crisis is bringing misery to tens of millions of working people. But it is also bringing us a new opportunity to get rid of a system that is continually rocked by such crises. The financial crisis has caused so much panic in the financial world that the fundamental instability of capitalism is being acknowledged openly on the front pages and the op-ed columns of leading newspapers. We may soon be in a situation in which great numbers of people begin to search for an explanation of what has gone wrong and a different way of life. At the moment this possibility might be remote, but revolutionary socialists still need to prepare for it. We need to be prepared with a clear understanding of how capitalism works, and why it cannot be made to work for the vast majority. And we need to get serious about working out how an alternative to capitalism—one that is not just a different form of capitalism—might be a real possibility.

Notes

1: Editorial note: this article (a substantially revised and updated version of Kliman, 2008) was written on 23 August 2008 and therefore pre-dates the effective nationalisation of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac by the US government.

2: Robert J Shiller, “The Fed Gets A New Job Description”, New York Times, 6 April 2008, www.nytimes.com/2008/04/06/business/06view.html

3: Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, “Dow Dives As Paulson Rules Out Rescue Of Loan Banks”, Daily Telegraph, 12 July 2008.

4: “Soros Says Fannie, Freddie Crisis Won’t Be The Last”, Reuters, 14 July 2008.

5: Peter S Goodman, “Uncomfortable Answers To Questions On The Economy”, New York Times, 19 July 2008, www.nytimes.com/2008/07/19/business/economy/19econ.html

6: John Spence, “Former FDIC Chief Urges Breakup Of Fannie, Freddie”, MarketWatch, 21 July 2008, http://tinyurl.com/6llagc

7: Peter Macmahon, “Worst Is Yet To Come In US Warns Rogoff”, Scotsman, 20 August 2008, http://business.scotsman.com/economics/Worst-is-yet-to-come.4406371.jp

8: Paul Krugman, “The B Word”, New York Times, 17 March 2008, www.nytimes.com/2008/03/17/opinion/17krugman.html

9: For instance, former chair of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Seidman has stated, “For all practical purposes, Fannie and Freddie are nationalised”. See John Spence, “Former FDIC Chief Urges Breakup Of Fannie, Freddie’, MarketWatch, 21 July 2008, http://tinyurl.com/6llagc

10: Dunayevskaya, 2000, p258 onwards.

11: Kliman, 2008.

12: Stephen Labaton, “Scramble Led To Rescue Plan On Mortgages”, New York Times, 15 July 2008, www.nytimes.com/2008/07/15/washington/15fannie.html

13: This does not mean that workers are all paid the value of their labour power. There is a stratification of wages, and the trajectory of wages depends on many factors. The point is rather that tax changes tend to be offset by other factors, so that standards of living remain more or less at their prior levels when all is said and done. That “who directly pays the tax” and “who bears the burden of the tax” are completely different matters (for instance, that landlords directly pay property taxes, but renters are ultimately the ones to bear the burden, in the form of higher rents) is one of the best known principles of economics.

14: Vikas Bajaj, “Housing Lenders Fear Bigger Wave Of Loan Defaults”, New York Times, 4 August 2008, www.nytimes.com/2008/08/04/business/04lend.html

15: Bob Ivry, “Zillow: 29% Of Homeowners Have Negative Equity”, Arizona Daily Star, 13 April 2008.

16: In principle these ratios could rise because of slower income growth, rather than because of a faster pace of mortgage borrowing, but that is not the case here. After-tax income increased by almost exactly the same average rate during the 2000-5 period as it did in the 1990s.

17: Quoted in “The Dis-integration Of The News”, economicprincipals.com, 30 March 2008, www.economicprincipals.com/issues/2008.03.30/311.html

18: Meredith Whitney, television interview on CNBC, 4 August 2008.

19: Geoff Colvin, “The Next Credit Crunch”, Fortune, 20 April 2008, http://money.cnn.com/

2008/08/18/news/economy/Colvin_next_credit_crunch.fortune/

20: “Treasurys Fall On Worries About Fannie, Freddie”, available from www.fkcp.com/?p=6770 posted 12 July 2008.

21: Quoted in Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, “Dow Dives As Paulson Rules Out Rescue Of Loan Banks”, Daily Telegraph, 12 July 2008.

22: Marx, 1991, p569.

23: “For A New Economics”, The Nation, 1/8 September 2008, www.thenation.com/doc/20080901/editors

References

Dunayevskaya, Raya, 2000, Marxism and Freedom (Humanity Books).

Kliman, Andrew, 2008, “Trying to Save Capitalism from Itself”, 25 April 2008, http://marxisthumanismtoday.org/node/13 and www.thehobgoblin.co.uk/2008_11_AK_Economy.htm

Marx, Karl, 1991 [1894], Capital, volume three (Penguin). An alternative translation is available online at www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1894-c3/